Looking back from the future, what will they think of us?

A Dig

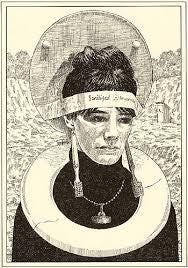

“The Headband, which bore the ceremonial chant, and the Sacred Collar (see illustration at end of reading) were still in place on the Sacred Urn to which they had been secured following the ceremony. The Headband was worn primarily to hold the sacred collar in place. The inscription on the front of the band was the holy chant; the language was atonal, and the words were pronounced more or less as follows – San-i-ti-zed foryo-urp-rot-ection…”

— Motel of the Mysteries, excerpt, by David Macauley

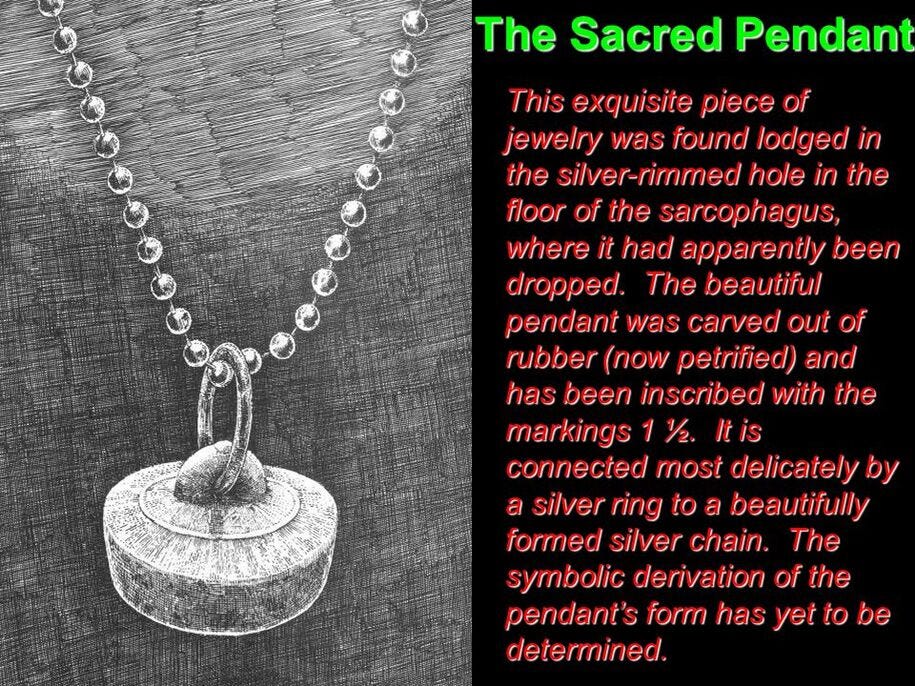

If you are of a certain age, you might remember a droll 1979 satire written by David Macaulay. I recall coming across it — maybe in a condensed version in Reader's Digest— and using it in my classroom as a discussion starter. Macauley’s little tale was both humorous and insightful. For those who are not acquainted with the short piece, its pen and ink drawings are essential to the humor, while the text illuminated one of the growing issues of the day— pollution. One drawing seared in my memory is of a woman wearing what Howard Carson, Macaulay’s dedicated archeologist, guesses is a Sacred Collar with its inspirational headband and fetching dangling earrings sure to inspire a smile (see above).

Despite his earnestness, the archeologist’s interpretation of our culture circa 1980 seemed silly while unleashing a frontal attack on our fascination with our culture’s less-than-critical, less-than-honest view of our own importance.

Macauley’s satire pretends that an archeological dig in 4022 unearths a 1980s strip mall motel buried under years of accumulated air pollutants that suddenly fell to ground due to its weight and the effects of gravity. Carson misinterprets its artifacts based on an assumption that the motel rooms are sarcophagi. Macaulay was most likely riding the wave of the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibit that began touring U.S. galleries with 55 “King Tut” artifacts in 1977. Many of us were quite taken by the more familiar Steve Martin parody from Saturday Night Live circa 1978.

I wonder how a future archaeologist would interpret the politics of our current cultural artifacts as they stumbled upon a buried time capsule with social and political objects that were defined by our time— the digitized videos and photos of our most powerful pols who ignored the looming destruction of our own civilization because of their ominous indifference. Would the weekly massacres that visited our era be seen as forms of religious sacrifice, the ones at schools as offerings to appease the wrath of our gods? Would the omnipresent artifact called the AR and numbered “15” be a representation of some sort of sacred totem used in religious services by high priests and their acolytes to ward off evil? Was the god we worshipped a vengeful god who spiked our free will with a lethal dose of stupidity?

Exceptionalism

We are in many ways a culture that is full of itself. We subscribe to a self-satisfying concept of American Exceptionalism that in many ways has become destructive. When it is invoked by our current crop of right-wing demagogs it becomes a mantra that allows who we are to excuse what we do. As such, the term invites the cognitive dissonance that leaves unexplained the ways in which we have been less than exceptional in our governance.

Frenchman Alexis De Tocqueville first noted the uniqueness of the American experiment and viewed it against the background of the rest of the world in the 1830s:

The position of the Americans is therefore quite exceptional, and it may be believed that no democratic people will ever be placed in a similar one. Their strictly Puritanical origin, their exclusively commercial habits, even the country they inhabit, which seems to divert their minds from the pursuit of science, literature, and the arts, the proximity of Europe, which allows them to neglect these pursuits without relapsing into barbarism, a thousand special causes, of which I have only been able to point out the most important, have singularly concurred to fix the mind of the American upon purely practical objects. His passions, his wants, his education, and everything about him seem to unite in drawing the natives of the United States earthward; his religion alone bids him turn, from time to time, a transient and distracted glance to heaven. Let us cease, then, to view all democratic nations under the example of the American people.

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Vintage Books, 1945

Who would have thought that the exceptionalism so appreciated by de Tocqueville would wither in an environment that valued the status quo or worse? If de Tocqueville were a prophet, he would likely identify 21st-century Republican political theory as much the same as he saw us then. He would most certainly recognize their puritanical underpinnings and a conveniently judgmental view of godliness and the outsized place of religion that exists in their politics. The reality of the MAGAN vision of America appears completely absorbed in the practical absurdity of retaining the past as a testament to self-sustaining perfection. It allows them a memory that excludes all the bad that existed in “the good ole days.”

Vision

What de Tocqueville couldn’t see from his 200-year-old vantage point was that American Exceptionalism, if it ever existed, was inherently impermanent, it had to evolve. The wisdom that attends to new knowledge and discovery is organic. Change doesn’t just happen, it is an inevitable.

Looking back on our present day from some point in the future is a trick futurists know as vision. It is not hard for us to envision an appraisal of our times as anything but exceptional— the undeniable brilliance of our scientists, doctors, artists, and educators, is more than tempered by the ignorance of those who have power over them. Looking back, our descendants might mourn our tendency to be drawn earthward, stuck in a morass of political and ethical debris, much like Macaulay’s buried sarcophagus with many chambers whose inhabitants were found at rest, heads pointed to the heavens and feet planted firmly in their times:

When American fiction considers the end of the country, we tend to assume our own crude, arrogant form of domino theory: that when we go, everything else will swiftly follow into the abyss. Our agonizing about our fate is often just another way of explaining that we don’t believe the planet would last long without us.

But without ever addressing it directly, Macaulay puts the lie to that egocentrism. For all America’s been destroyed by this undefined catastrophe, in “Motel of the Mysteries,”

— WAPO, “In ‘Motel of the Mysteries’ America falls — and it doesn’t actually matter,” by Alyssa Rosenberg

A takeaway from Macauley’s satire is a lesson for us today. An assessment of some future political archeologists is far less worrisome than the truth that is evident in our politics today. We are in peril from the weight of our political pollutants that threaten to bury us in lies and deception. The future viability of our civilization depends on our ability to overcome the selfishness and coarseness that lies within us.